Introduction

After the Bible and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, The Divine Comedy has probably been the motivation for more paintings than any other literary work. Those span the period from the fourteenth century, when it was completed, to the present day, from Botticelli to Degas and beyond. This article is a general introduction, which will hopefully whet your appetite.

Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri, known as Dante Alighieri or simply Dante, was born in Florence in about 1265. The city-state was growing very rapidly at the time, and was a hotbed of the Renaissance. Its politics were dominated by two family-based factions, the Guelphs, to whom Dante was loyal, and the Ghibellines.

When Dante was only nine, he met and apparently fell in love with Beatrice Portinari, but at the age of twelve he was betrothed to Gemma di Manetto Donati, a member of the powerful Donati family. Beatrice, or Bice, remained a flame in his emotions, even after she died in 1290, and she inspired his Vita Nuova as well as much of The Divine Comedy.

The appropriately-named Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s painting of Dante’s Dream on the Day of the Death of Beatrice from 1880 is a good example of the attention devoted by the Pre-Raphaelites to Dante’s relationship with Beatrice, although much of this may have been imaginary, and based on courtly love.

In the late thirteenth century, the Guelphs were on the ascendant, and in 1289, Dante fought for them in the Battle of Campaldino, at which Ghibelline exiles from Florence were soundly defeated. But following this, the Guelphs divided into White and Black factions, in part over the role of the Pope in Florentine affairs.

Dante was deeply involved in Florentine politics, and rose to its highest position as a city prior. He was caught when in Rome on a mission to Pope Boniface VIII, and in 1302 was sentenced to perpetual exile for alleged crimes against the rival faction. If he were to return to Florence without accepting his ‘crime’ and paying a heavy fine, he faced being burned at the stake.

The poet spent the rest of his life in exile, completing The Divine Comedy in 1320, just a year before his death.

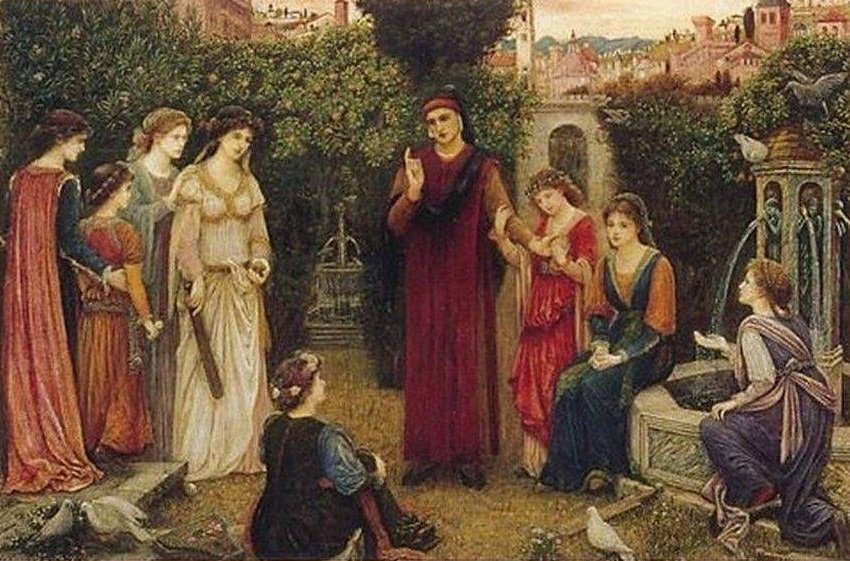

Marie Spartali Stillman’s superb watercolour of Dante at Verona from 1888 was one of three related works which she submitted for the inaugural exhibition of the New Gallery, and refers both to Dante’s exile and the poem of the same title by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. That poem is set in the public garden in Verona, where “wearied damsels” request the poet to recite his early poem Vita Nuova.

The Divine Comedy circulated after its completion, but it was Boccaccio who first promoted it and set it on the road to becoming one of the major European literary works of all time. The first printed edition appeared in 1472, and it has since been printed in a great many editions and translations.

The framing story of The Divine Comedy describes Dante himself visiting these three realms of the afterlife in the company of the shade of the Classical Roman poet Virgil (in Hell and Purgatory), and Beatrice (in Paradise). Each visit travels through a series of circles or levels in that realm, and each of those circles contains figures drawn from classical literature, legend, and Dante’s own life, who have committed various sins and are now suffering its consequences.

Marie Spartali Stillman’s superb watercolour of Dante at Verona from 1888 was one of three related works which she submitted for the inaugural exhibition of the New Gallery, and refers both to Dante’s exile and the poem of the same title by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. That poem is set in the public garden in Verona, where “wearied damsels” request the poet to recite his early poem Vita Nuova.

The Divine Comedy circulated after its completion, but it was Boccaccio who first promoted it and set it on the road to becoming one of the major European literary works of all time. The first printed edition appeared in 1472, and it has since been printed in a great many editions and translations.

The framing story of The Divine Comedy describes Dante himself visiting these three realms of the afterlife in the company of the shade of the Classical Roman poet Virgil (in Hell and Purgatory), and Beatrice (in Paradise). Each visit travels through a series of circles or levels in that realm, and each of those circles contains figures drawn from classical literature, legend, and Dante’s own life, who have committed various sins and are now suffering its consequences.

The poem is rich with references to stories of human weaknesses and failings. Jean-Jacques Feuchère’s Dante Meditating on the “Divine Comedy” from 1843 captures this particularly well, with Dante sitting at work in the midst of the many spectres he invoked in its lines.

From the start, when Dante and Virgil set off on their journey, every moment has been painted or drawn, often by major artists. Corot’s Dante and Virgil from 1859 was exhibited that year at the Salon, but then lay forgotten in his studio. When he rediscovered it in the early 1870s, he was so impressed with his work that he offered it to the French state. It wasn’t until after Corot’s death that it was finally sold, to the Boston collector Quincy Adams Shaw.

Dante and Virgil at the Entrance to Hell is one of Degas’ early narrative paintings, made in about 1857-58 when he was still in Italy. At about the same time, the great French illustrator Gustave Doré started the first of his long series of paintings and engravings of Dante’s poem.

The sinners in Hell are divided according to the type of sin; here, Doré shows Virgil (left) and Dante at the last of these circles, the ninth, for those who committed sins of malice, such as treachery. These sinners are shown partially frozen into an icy lake, with additional blocks of ice scattered around, just as described by Dante.

In 1822, the young Eugène Delacroix painted one of his finest narrative works, The Barque of Dante, showing Dante and Virgil crossing a stormy river Acheron in Charon’s small boat.

Ever since Dante completed The Divine Comedy, enthusiasts have been drawing charts and maps of its realms. Botticelli’s Map of Hell from 1480-90 is perhaps one of the most famous, with its detailed depiction of each of the circles described in the poem.

Another major artist who had a longstanding obsession with Dante’s poem is William Blake. At the end of his career, he was commissioned by the artist John Linnell to produce a set of illustrations, which remained incomplete at the time of his death in 1827. The Punishment of the Thieves (1824–7), anticipates figurative painting of a century or more later, and the darker psychological recesses of sex and snakes. Dante refers to the thieves being bitten by snakes, but Blake uses the creatures in other ways.

Blake’s most famous and wondrously imaginative of these illustrations shows The Circle of the Lustful: Francesca da Rimini, which he completed in about 1824, and had already been etched when the artist died.

This shows one of Dante’s best-known and probably largely original stories, of the adulterous couple of Francesca da Rimini and her lover Paolo, her husband’s brother, who were both murdered when caught in bed together by Francesca’s husband.

Ary Scheffer’s vision of Dante and Virgil Encountering the Shades of Francesca de Rimini and Paolo in the Underworld from 1855 is more conventional. This is one of Scheffer’s most brilliant narrative paintings.

In this series, I will concentrate on paintings and other works of visual art which are directly related to Dante’s words. The latter were also of immense influence in other works of art from the fourteenth century onwards.

Tintoretto’s last vast painting, seven metres (almost twenty-three feet) high and twenty-two metres (over seventy feet) across, showing Paradise (1588-92), focusses on the Coronation of the Virgin, but was inspired largely by Dante’s description of Paradise.